Should principals be operational experts?

Instructional leadership has crowded out other critical skills for leaders

During my principal certification program, I spent five intensive weeks immersed in understanding rigorous, Common-Core-aligned teaching. Myself and 30 other aspiring principals watched videos of teachers, submitted ratings of their lessons, and discussed our scores to better align our visions of high-quality instruction.

In a separate notable principal-development program, I spent two intense weeks plus four full weekends doing the same, this time diving deeper into actual student work and teachers’ lesson plans. We analyzed how lesson plans aligned with the intent of the standards, then evaluated student work to determine exemplar responses for reading and math standards.

I often think of the principal role as having four major areas of focus: instruction, school climate, family & community engagement, and operations. Each is critical to the efficient and effective functioning of a school, but leadership development has evolved to focus almost exclusively on the first — instruction — with the occasional nod to the importance of school climate and little time set aside for the last two.

Take, for example, the principal PD week this very August. I sat through 20 sessions on topics ranging from how to lead teacher planning time, prioritize community circles, and navigate new math and literacy frameworks. Of those 20 sessions, just one focused on operational leadership.

This scant attention paid to operational isn’t unique to Philadelphia. All across the country, books and websites and workshops and consultants are pushing principals out of their offices and into classrooms.

The theory of action is simple: high-performing schools prioritize great instruction, and by regularly observing, rigorously rating, and steadfastly coaching (what an adverbial trio!) teachers, principals could turn any underperforming school into an instructional powerhouse. It’s the principal-as-instructional-leader theory, and it’s been the driving force behind how we hire, coach, and retain principals.

This reflects a shift that’s occurred over the last two decades in how the principal role is viewed. In the past, principals were often viewed as “building mangers,” ensuring that school ran smoothly each day. Rarely, if ever, would they be in classrooms or deeply involved in instruction. Instead, they’d be burrowed in their office engrossed in administrative work.

The shift is, at its core, a good one. Steve Jobs couldn’t have transformed Apple without a distinct vision for its products and a tireless devotion to their perfection. The core product schools offer is instruction, and principals should also be focused on making sure it is of the highest quality.

And still I worry that we’ve de-emphasized operations so much so that it’s interfering with our ability to focus on our core product.

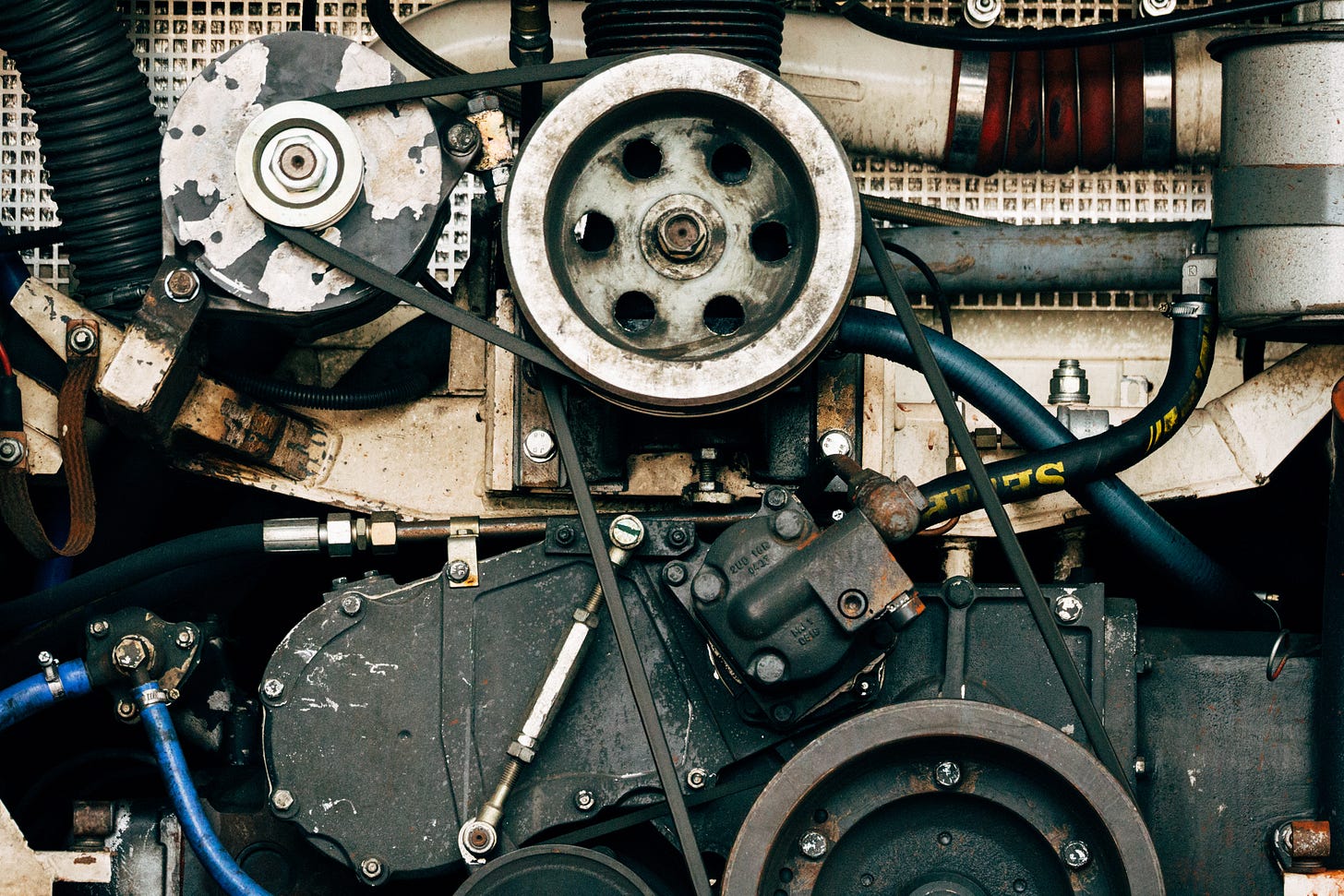

Operations in a school — from staff culture, payroll procedures, student registration, staff retention practices, investigating incidents, procurement, school-wide routines for admit, dismissal, lunch, and recess, fire and shelter-in-place drills, and facilities management, to name a few — are complex work. I’m feeling more than inadequate in handling all the operational challenges this year.

Key information for most operational procedures is overviewed in a 51-page reference manual. Ten pages are devoted to health and safety protocols. Another two to technology. But the 51 pages are misleading. The document contains links to other lengthy documents — the finance manual itself is 52 pages — and little time is set aside to immerse principals in the manual and its many manual relatives, and that can be problematic.

When lunch service doesn’t run smoothly, for example, kids don’t have enough time to eat. Empty stomachs beget understandably distracted students, annoyed teachers, and upset parents, and dealing with those consequences can eat up precious hours I’d otherwise spend in classrooms. Instruction suffers indirectly.

Earlier this August we had to prepare for a new daily schedule — school would start an hour earlier than ever before — 7.30AM. This required us to reconfigure our admit procedures, breakfast service, and staff schedules — a massive time investment with little guidance. The early start time also meant an earlier dismissal: parents now had to pick their children up at 2.09. This led to two minor crises we weren’t prepared for: a desperate need for earlier childcare and a conflict with the public transit depot across the street. Their buses depart at the exact time hundreds of families were idling to pick up their children. An operational conundrum for which the 51-page manual offered no solutions.

Thanks for reading. Have a great week.