Can grammar help end The Achievement Plateau?

Aaannnddd....I'm back!

Dear Readers, it’s been nearly 3 months since my last post, and these are my sins…

School has been busy. Turns out getting a doctorate at Harvard requires a lot of reading and writing. Who knew?

Raising kids is exhausting (and great!). My wife and I haven’t slept through the night since July nor had a fever-free week since October. But the boys are healthy and in school (daycare) today.

I wrote and submitted my last final on Friday, and I’ve got a few weeks until classes resume, so I’m excited to start writing again.

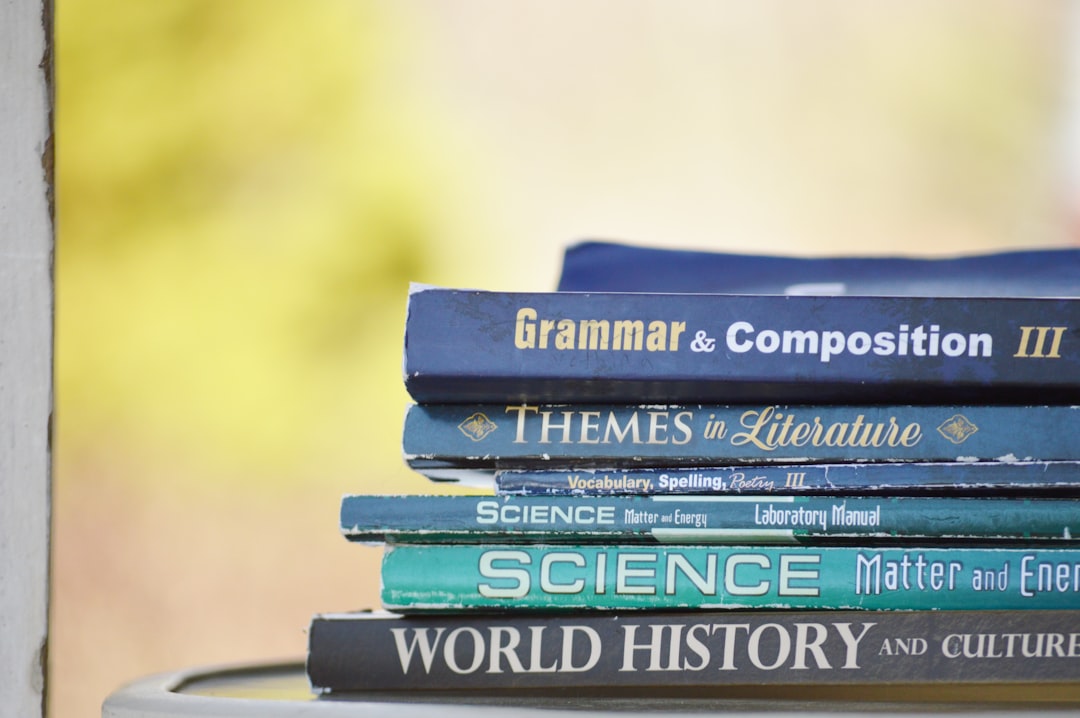

What better topic to restart this newsletter (blog?) than grammar. Well, not grammar grammar, like the kind you learned in language arts class if you went to Catholic School like I did.

Rather, I’m talking about what David Tyack and Larry Cuban call the “grammar of schooling” in Chapter 4 of their seminal text on education reform, Tinkering Towards Utopia. Among the thousands of pages I’ve read this semester, I highly encourage this one if you’re interested in exploring the history of education reform.

The “grammar of schooling” refers to the traditions that dictate how school looks and feels, from the way grades are organized by age, to the way subjects are sectioned off and taught in isolation, to the way grades are assigned and students are seated. As Tyack and Cuban note, the “grammar of schooling” has remained “remarkably stable over the decades.”

Aside from swapping Tandy 2000s for Macbook Airs and trips to confession for trips to the museum, the K-8 school I led up until June of 2022 looked almost identical to the K-8 school I attended until June of 1996.

This template for schools has been difficult to revise. As Tyack and Cuban note, innovations to create ungraded schools, utilize space in a flexible manner, merge subjects, and encourage teacher collaboration have mostly been stymied.

Consider the history of the graded school, in which students are organized by age-bound grades. Despite early concerns that it might lead to more drop-outs and a narrow curriculum focused on end-of-year tests, it has stood the test of time since the 1870s after making obsolete the one-room school and the large, mixed-age classroom led by a master teacher.

One of the more famous attempts to rethink the graded school was the Dalton Plan, developed in the 1920s by Helen Parkhurst, a teacher and school founder who was heavily influenced by Maria Montessori. The Dalton Plan focused on elevating student choice, with monthly contracts that outlined the minimum tasks students had to complete, as well as optional, enrichment tasks. Students went to laboratories (not classrooms) to complete their activities, and their progress was displayed on large charts showing their content mastery. At its high in the 1930s, several hundred schools followed the Dalton Plan, but it had all but disappeared by 1949.

So why is it so hard to sustain these innovative approaches to schooling, especially when so few of us deeply love the rigid structure of the current grammar of schooling and the system as a whole continues to underwhelm? Tyack and Cuban identify two common challenges: reform burnout and lack of political savvy. Changing the grammar of schooling requires enormous effort from educators to change their practice and that of students. It also requires support from citizens outside of education, many of whom get politically aggressive when traditions are threatened. Just look at the current outrage regarding Critical Race Theory and related book banning efforts.

Changing what happens inside schools is incredibly difficult. Nearly every student, teacher, parent, school board member and citizen has an imprint of what school should like (the one they attended as a child!). Attempts to deviate from that template might garner some interest but fade quickly. If we’re going to end The Achievement Plateau, though, we’ve got to do something different. And while the grammar of schooling might be intractable, I’m wondering if the grammar of central offices might be more malleable. More on that soon.

Thanks for reading. Have a great week. Go Birds.